Nuclear Command and Control Issues

Having an unstable president isn't the worst thing

With President Donald Trump assuming his authorities as commander-in-chief of U.S. military forces, many of his critics will inevitably air concerns about his state of mind when dealing with immediate nuclear crises. In his first term, I don’t think he was that focused on nuclear issues. Yes, he talked about his big red button and he stressed the power of “the nuclear” as if that was how normal people talked about nuclear weapons. But he didn’t seem to be that interested in the details. I don’t for instance think he was that engaged in drafting the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review, call me crazy. I’m not so sure in this second term. His advanced age and lessened mental acuity, combined with a narcissistic edge to push right past international norms, has me concerned but not dismayed. I do not have any faith that this president or his newly-appointed SecDef understand or appreciate contemporary nuclear threats and how to deal with them. There should be enough conservative nuclear hawks around him to stop any preventive first strikes against nuclear-armed states, at the least.

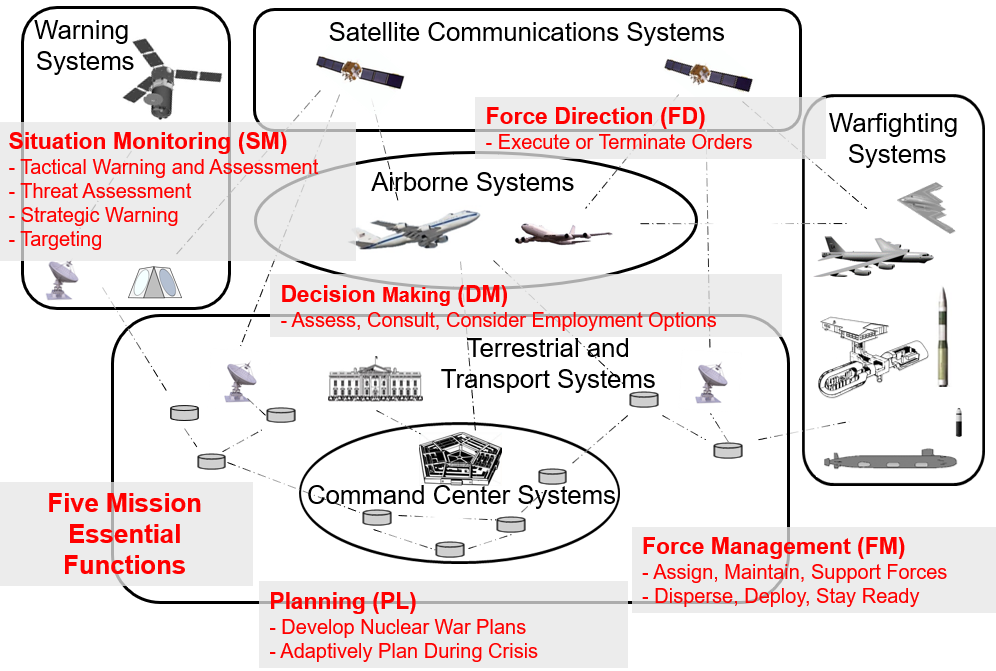

I also acknowledge that there may be more visible, near term challenges regarding the president’s new directives - placing singularly unqualified people in positions of leadership at the top of DoD, DoJ, DHHS, and the intelligence community, withdrawing from the World Health Organization and Paris Accords, ignoring a congressional law banning TikTok, ending birthright citizenship, sending thousands of active duty troops to the southern border to block a nonexistent “invasion,” rounding up undocumented immigrants while releasing insurrectionists from prison - these are all remarkably bad decisions that are eating up media air time. But since I cover nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons issues, I thought I’d circle around back to this topic. Nuclear command, control, and communications (NC3) is a very complicated “system of systems” that involves over two hundred different ground, airborne, and space systems working in tandem to ensure that the president (and only the president) can launch nuclear weapons when he or she authorizes such use and not launch when said authorization has not been given. This CRS primer has a good brief on the topic.

“U.S. [NC3] is necessary to ensure the authorized employment and/or termination of nuclear weapons operations, to secure against accidental, inadvertent, or unauthorized access, and to prevent the loss of control, theft, or unauthorized use of U.S. nuclear weapons.”

NC3 can be discussed as a major defense acquisition program, a political process by which presidents exert “positive control” over nuclear weapons, and with respect to the unknown challenges of artificial intelligence systems that might be employed within this system. It’s difficult to discuss any particular hard facts due to classification issues and the lack of any particularly sexy defense systems, but it’s worth examining the broad topics that define the challenges in this area.

Five Essential Functions of Nuclear Command, Control, and Communications

About 10 years ago, the Air Force (which owns most of the NC3 systems) got serious about managing this function as a single weapon system, recognizing that there was no single organization overseeing NC3 integration. That had obvious implications in sustaining and modernizing the many, many programs that were all networked together for a unique role. Back then, the concern was more about the need to prevent any hacking into the secure lines of communication. The Air Force put together a governance process over the acquisition and development of NC3, designating it as “AN/USQ-225” as a way to manage it under the Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center.

One of the more visible components of the Air Force’s NC3 is its E-4B Survivable Airborne Operations Center or the “doomsday plane.” This is the plane that acts as a mobile command center for the president and defense staff during national emergencies. The Air Force recently established the 95th Air Wing at Offutt AFB to consolidate all of its air-based command and control units under one organization. One of its functions will be to manage and oversee the development of the E-4C SAOC, a $13 billion program designed to replace its 1970s-era predecessor.

The Air Force Global Strike Command had set up an NC3 Center at Barksdale AFB in 2016 to oversee the development and integration of 62 AF-budgeted NC3 projects. This center closed in 2021 as USSTRATCOM stood up its NC3 Enterprise Center at Offutt, which promised to eliminate the Air Force and Navy stove piped acquisition programs. According to the CBO, the DoD will spend about $117 billion between 2023 and 2032 on NC3 systems, as compared to $389 billion for the delivery systems and weapons and $143 billion for the nuclear weapons labs and supporting activities. This figure includes operations, sustainment, and modernization costs. This assumes, of course, that the programs will stay on cost and on schedule (*cough* SENTINEL *cough cough*).

Hardening the NC3 from cyber threats has been the most immediate concern, and there has been a specific program to improve this capability. The Director for Operational Test and Evaluation has a few notes on this in its 2023 report.

[Cyber Assessment Program] CAP and USSTRATCOM continued a partnership for assessing and improving the cyber survivability of NC3. The complex nature of the hybrid legacy and modernized system-of-systems that comprises NC3 poses challenges to assessments of this mission space, however, progress is being made across the NC3 enterprise as a result of the continued partnership. Barriers to cyber assessments of the NC3 enterprise include a lack of operational capacity to support operations and testing simultaneously, as well as ongoing modernization efforts.

CAP is sponsoring the development of a high-fidelity virtualization environment for a subset of NC3 legacy systems. This environment will assist with assessments and Red Team activities that would otherwise be challenging on the operational networks. Once validated, the environment will also help assess and experiment with improved cybersecurity defenses and allocation of sensors deployed across the transitioning NC3 systems-of-systems.

The urgent need to improve and sustain NC3 may not be appreciated, largely because of the high levels of secrecy and lack of flashy industry promotions. This is a significant risk that, in the course of leader development and education, it could be overlooked or minimized (as nuclear issues had been in the past). The Air Force Institute of Technology has a School of Strategic Force Studies through which it offers professional continuing education programs for nuclear operators and NC3 operators. Given the complexity of the mission and the need to develop operators throughout their career in this very technical area, Congress directed in 2019 that there needed to be “a plan to train, educate, manage, and track officers in the Armed Forces” in NC3 activities. These PCE courses are taught at Barksdale AFB. NC3 is not a topic at the service war colleges, though. It’s a little too technical and too niche.

There are so many moving components within this acquisition program and the details of each would be boring,1 so let’s move on to talk about the process of presidential launch authority. This became a hot topic about six-seven years ago, for no apparent reason whatsoever.

We’ve always had this scenario of a no-notice surprise Russian strategic attack as the primary rationale for stating that the U.S. president needs the sole authority to decide when and whether to use nuclear weapons. Given that there could be Russian ballistic missile submarines off the U.S. coasts and that Russian ICBMs could be hitting U.S. soil within 30 minutes, there’s been a (reasonable) concern that time would be of the essence to make a firm decision. If the president does not immediately act, then it’s a strong possibility that the 400 missile siloes will be targeted and taken out, not to mention the few strategic bomber and ballistic missile submarine ports. As this is a political decision of the highest order, having the commander-in-chief make the call (after receiving military and political advice) would seem to be prudent.

Except of course, we have massive ICBM fields designed to be a “sponge” for just this situation, and we will always have deployed ballistic missile submarines to provide an “assured second strike.” There are other mitigating factors to ensure that NC3 will survive a nuclear attack as well (notably, redundancy and hardening). Given these facts, there is no compelling reason that the president has to “use it or lose it” with regard to a no-notice attack. The national command authority could always ride out a strategic nuclear attack to ensure that this wasn’t a computer glitch due to bad data at an early warning radar site or an accidental launch that only involves one or two inbounds. The U.S. second strike does not have to happen immediately on the same day as an adversarial attack. On that basis, nuclear weapons critics have called for an end to the policy of a single authority to launch all U.S. nuclear weapons.

You can read the proposed reform approach that the Arms Control Association suggests in this brief that came out in 2018 (I’m sure it’s a complete coincidence that Trump was ranting about North Korea’s nukes at the time). I strongly suspect that a similar argument will arise again in 2025. There’s some rationale in the idea that, in the event that the U.S. president wants to conduct a “first strike” against another nation, the congressional chairs of the armed services committee might at the least be consulted for their views prior to any decision to launch a nuclear weapon. Congress could demand that, in the absence of an immediate and existential threat to the United States, the president should consult with them prior to using a nuclear weapon. Then again, I’m not sure this Congress would be of any assistance in this matter, given the unswerving fealty of this Republican party to the president.

It’s a valid point, however, and serious people in the Beltway ought to discuss how the president uses his nuclear launch authority. Most of the national security community take it for granted that the way nuclear actions were done during the Cold War still applies today, because the (basically) same delivery systems exist. Why change the protocols today when things have been working so well for so long? But this is a lazy attitude, that because nuclear crises so rarely emerge, we shouldn’t evaluate how the most likely cases of nuclear posturing and escalation ought to be handled and adapt our nuclear posture to the speed and ambiguity of current international affairs.

Last, there’s the question of whether the United States should use AI to direct nuclear launch sequences, because we can’t trust the man-in-the-loop to turn the key when they receive an order to launch.

I love this film clip - the amazing John Spencer and Michael Madsen as missileers in a launch control center. If you haven’t watched the 1983 “War Games” in addition to “Dr. Strangelove” and “Fail Safe,” are you really even serious about nuclear weapons?

I will suggest that any discussion of how artificial intelligence will impact highly technical fields such as nuclear weapons use, biotech research, and chemical weapon design will be highly speculative. Of course, that won’t (and should not) stop people from discussing the possibilities of what could happen and what guiderails ought to be put into place. This article’s authors call for introducing AI into the NC3 process to decrease the time between detection of an adversarial launch and the decision to retaliate. In particular, they suggested a “Dead Hand” system for the United States.

It is easily conceivable that attack-time compression will reorder this process: the president will decide ahead of time what response will take place for a given action and it will then be left to artificial intelligence to detect an attack, decide which response is appropriate (based on previously approved options), and direct an American response. Such a system would differ significantly from the Russian Perimeter system since it would be far more than an automated “dead man” switch — the system itself would determine the response based on its own assessment of the inbound threat.

Unsurprisingly, there were a number of critics of this approach. I don’t know of any serious scholars of nuclear deterrence who believe that AI should be making judgment calls with regards to nuclear targeting and launch approval. At the same time, General Tony Cotton, current USSTRATCOM commander, sees some value in putting AI into the NC3 process.

Growing threats, an overwhelming flow of sensor data, and increasing cybersecurity concerns are driving the need for AI to keep American forces a step ahead of those seeking to challenge the U.S., Cotton said. “Advanced systems can inform us faster and more efficiently,” he explained. “But we must always maintain a human decision in the loop to maximize the adoption of these capabilities and maintain our edge over our adversaries.”

Cotton said AI can help give leaders more “decision space” to ensure the entire nuclear enterprise stays secure. “Our adversaries must know that our nuclear command and control and other capabilities that provide decision advantage are at the ready, 24/7, 365 and cannot be compromised or defeated,” Cotton said.

He seems to agree with the general idea of using AI to reduce the time needed to assess adversary capabilities and actions involving nuclear weapons. Both he and the WotR authors quoted above seem to believe that there is a competition going on to field a superior AI capability that “allows for more effective integration of conventional and nuclear capabilities, strengthening deterrence.” I’ll go back to my usual position to say that deterrence between two nuclear power states is not just a function of capability and credibility, but of successfully communicating a threat to an adversary that its actions will not benefit its proposed outcome. I don’t know how, in any capacity, the United States would convince Russian and Chinese leaders that it had a superior nuclear detection and launch process because of “AI superiority.”

I’ll leave it to others to argue the fine points of how AI might enhance NC3 during a national emergency. I’m skeptical. Maybe there’s a limited role in using AI to evaluate adversary data and assess emerging threats but there’s no call for a “Dead Hand.”

Nuclear command, control, and communications is a very complex topic with no end of interesting discussions. There’s something for everyone, the defense acquisition reformists, the political decision-making process of the national command authority, and the frightening “what if” discussions of artificial intelligence. There have been a number of recent studies on NC3, but I’ll suggest that not much has changed since the 1980s as far as its general construct as the backbone of the U.S. nuclear posture. I’m not sure it will ever change, but at the least, we ought to ensure that it’s modernized to the point that no one can hack into it and that the operators are well-trained to ensure that it works to not launch if the president does not give authorization to do so.

Let me recommend this book edited by James Wirtz and Jeffrey Larsen, “Nuclear Command, Control, and Communications: A Primer on US Systems and Future Challenges,” Georgetown Univ Press, 2023, for a more in-depth discussion.

A colleague reminded me to mention the Navy TACAMO, an important part of the NC3 system - https://www.navy.mil/Press-Office/Press-Releases/display-pressreleases/Article/4011344/navy-awards-3459276000-contract-to-northrop-grumman-systems-corporation-to-deve/

When do we get to address the question of what if SecDef is drunk when he gets the order, or even just when he has to approve the memo to make all this stuff happen?