Catching Up on Nuclear Operations

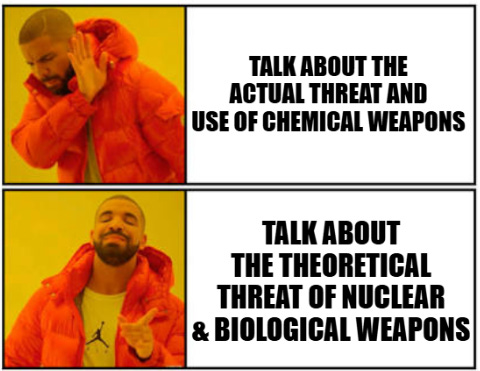

Because everyone loves talking about nuclear warfare

A good while back, while I was still working as an Air Force professor, I found a course syllabus that was used at the Air Command and Staff College. It was titled “Biological and Nuclear Weapons: Challenge and Response,” and I thought, well, that’s just short-sighted. Why leave out chemical weapons? Why not just say “Combating Weapons of Mass Destruction”? There was an easy answer that I didn’t want to acknowledge, in that no one really cared about addressing chemical weapons threats. It wasn’t a priority, despite the contemporary use of chemical weapons by Syria and Russia on a battlefield, not to mention North Korea’s chemical weapons stockpile. There’s no recognition on how easy it would be for a disgruntled person or group to use industrial chemicals in a domestic terror attack, leading to a mass casualty event. The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency says that there are more than 11,000 chemical manufacturing facilities in the United States, moving more than three billion tons of hazardous materials every year. No, no worries there. The priority remains on the existential threat of those unconventional weapons that have not been actually used since 1945.1

This fits a pattern that I have had to adapt to, in that if I want to talk about unconventional weapons on a weekly basis, it’s going to be to comment on news articles and academic studies about nuclear and biological weapons much, much more than chemical weapons. If you readers see any chemical weapons news, please forward it to me. I’ve been talking a lot about biological weapons lately, so it’s time to catch up on what’s going on in the nuclear weapons business. In particular, I’m going to highlight the Air Force’s new publication on “Nuclear Operations” and a GAO report looking at the Sentinel ICBM program.

Since the Air Force controls two-thirds of the nuclear triad, its nuclear community spends a lot of time talking about nuclear deterrence operations. They don’t have much new to say, but they do publish a lot of pieces and show fancy videos about their hardware. The Air Force Doctrine Publication 3-72, titled “Nuclear Operations,” has not always been around. There was a gap for several years in which the Air Force had not showcased such a document, but over the last few years, it’s been updated and released for general information. The Air University released a short video that highlights the most recent update.

It’s not a great video in that it just repeats some of the major themes of the publication, but I suppose that’s the purpose, to draw in the people who might be interested in this particular doctrine. To be fair, the publication is well-developed, if not short, considering this is the unclassified concept of how the U.S. Air Force exercises nuclear deterrence operations. There’s a short chapter on the basics of deterrence theory, a really inadequate discussion of nuclear weapons effects (basically could fit on a postcard), and an introduction to the concept of supporting a theater of conflict with nuclear operations. This was an eye-opener for me:

To achieve theater-level objectives, CCDRs may request the use of CONUS-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) or theater-level nuclear weapons using either long-range bombers or fighters designated as DCA capable of both nuclear and conventional operations. Cruise missiles allow for standoff attacks, which puts crew members at minimal risk and may deny an adversary significant tactical warning. Gravity bombs allow more flexibility in employment but put crew members at direct risk in a high-threat environment.

I’m sorry, what? I get the strategic bombers and DCA use2 of “low-yield nuclear weapons” but I’m sorry, we’re not going to launch a strategic nuclear weapon against an adversary in which the U.S. military is engaging in a conventional operation. Come on, Air Force, you’re basically making Annie Jacobsen’s (poorly articulated) point that U.S. nuclear strategy is fucked. I’m hoping there’s a logical explanation for this stupidity. Chapter 2 goes into AF nuclear forces to talk about how the ICBMs, strategic bombers, DCA, and the nuclear command, control, and communications (NC3) support The Triad. A little surprised that they didn’t include at least one paragraph for the submarines. Yes, I know this is about the Air Force systems, but if you’re going to explain nuclear operations, kinda important to ensure you cover all the bases. At least, that’s what we used to teach at the Air University.

The third chapter on commanding nuclear operations is good for people (even in the Air Force) who don’t understand the significant chain of command required to control nuclear deterrence operations. Be warned, it’s very heavy with acronyms and the lack of a flow-chart is disturbing. Interestingly, they take the time to explain the difference between NC3 and NC2, the former being the hardware that makes up the command management aspects and the latter of which is “the exercise of authority and direction by the President.” Chapter 4 goes deeper into the nuclear planning and execution, which includes the possibility of a joint force engaging in conventional-nuclear integration. This is one of my heaviest pet peeves, because I don’t think that people outside the AF nuclear enterprise can read between the lines here.

Conventional-nuclear integration (CNI) is the ability of the joint/combined force to recognize and survive the use of nuclear weapons, reconstitute critical capabilities, and plan and execute integrated, multi-domain conventional and nuclear combat operations in, around, and through a nuclear environment. Conventional support to nuclear operations is conventional capabilities required to prepare the battlespace to ensure timely delivery of nuclear effects or to enhance or complement nuclear options.

Back in the Cold War, we would have just called this “warfighting.” This is a lot of fancy, extraneous words to say, “we intend to plan for the use of U.S. theater nuclear weapons in the context of a conventional conflict.” Ideally, this is intended to get the Air Force components of the geographic commands (in particular, USCENTCOM, USEUCOM, USINDOPAC) to develop plans including U.S. nuclear weapons use rather than just letting USSTRATCOM do all the work. Funny enough, even this publication notes that this might not happen. “While CNI may improve unity of effort, it may pose unity of command challenges.” You don’t say. Critics suggest that this lowers the nuclear threshold and increases the odds of escalation to a strategic nuclear strike. Let’s grant that the possibility of China, Russia, or North Korea conducting a theater nuclear strike exists. Exactly how will the Air Force integrate nuclear strikes into a conventional campaign and manage the escalation risk?3 I don’t believe that our military officers think about this enough to make CNI work as a concept. I’m not saying that CNI is a good or bad thing, as much as I say that I don’t think it is well-thought out and clearly explained.

The fourth chapter ends with an “assessment” phase that includes post-attack recovery and restitution, because we plan to continue fighting after the nuclear balloon goes up. In theory at least. There’s this paragraph.

US nuclear systems and facilities both in the homeland and overseas are lucrative targets. USAF forces should be capable of responding to and executing operations in a contaminated environment with minimal degradation of force effectiveness. Implementing the principles of CBRN defense—avoidance, protection, and decontamination—should help preserve the fighting capability of forces.

I’m sorry, I couldn’t help that. I’d note two things, first that no one in the U.S. military has used the terms “avoidance, protection, and decontamination” to describe the principles of CBRN defense since the 1980s. Second, the parties responsible for Air Force CBRN defense don’t believe in providing adequate capabilities to air bases to allow for “responding and executing operations in a contaminated environment” as evidenced by their lack of ability to leverage the CB Defense Program, given OSD bullying of the services.4 Third, the Air Force doesn’t practice unit-level CBRN defense operations as much as they just hope that chemical and biological contamination is not a significant threat to mission operations. It’s a sad joke. But no one in the AF nuclear operations shop really cares to engage the AF CBRN defense community to actually make this a viable concept.5

Chapter 5 is on nuclear surety, because the last thing that the Air Force wants is another unauthorized movement of nuclear cruise missiles from one air base to another. Nuclear surety is very technical and very complex but can be distilled into four components: the safety of storing and moving nuclear weapons, the security of nucellar weapons, the positive control over a weapon system’s use, and the reliability of the nuclear weapon system. Important stuff that results in very long technical checklists that must be strictly followed so as to ensure nuclear weapons are only used and will be used when the president says so.

That’s it. If you were to look at the Air Force’s nuclear operations doctrinal concept from 20 years ago, I don’t think it would look that different except for the CNI part. Let me say that this does not mean the Air Force nuclear doctrine is Cold War mindset. It is most assuredly post-Cold War and ultimately workable, given the parameters of the discussion. My concern is more the cold technical nature of the discussion and the lack of critical debates and reviews of how this actually works against an adversary that is a nuclear-weapon state. But we can’t have nice things like that. The AF nuclear enterprise is still very much a priesthood that jealously guards its secrets, and the rest of the Air Force leaves them alone.

Speaking about AF nuclear weapons, there’s the recent GAO report on ICBM modernization, to wit, the transition from Minuteman IIIs to Sentinels is not going smoothly. The GAO response is typical: “Develop a risk management plan to establish an organized, methodological way to identify assess, and respond to the myriad risks” of such an effort (the GAO loves performance plans and risk management plans). It’s a great report in that it identifies a lot about the ICBM program that people outside of the DoD nuclear enterprise might not appreciate.6 But you have to get through a lot of that data before getting to the meat of the issue.

When we asked about a transition risk management plan, Global Strike Command officials told us that, as a newly established office, Global Strike Command A10 is still working to hire personnel and establish project management processes. Officials emphasized that all transition planning efforts are currently under review or undergoing changes due to the Sentinel delays. The officials stated that Global Strike Command will continue to identify transition risks and develop risk mitigation strategies as the program matures leading up to the Sentinel Milestone B decision. In July 2024, the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment directed the Air Force to evaluate options to ensure a transition between Minuteman III and Sentinel that considers risk, mitigations, and trades across cost, schedule, and performance prior to receiving Milestone B approval. Global Strike Command officials told us in August 2024 that they are working on this task as the Air Force restructures the Sentinel program. However, as of September 2024, Global Strike Command has not identified specific documents, such as a written risk management plan, risk report, or risk register, to be developed in the forthcoming risk management planning efforts.

Congress told the Air Force to start planning for a MMIII replacement in 2006. The Air Force did its Analysis of Alternatives in 2014. They started the contract solicitation in 2016. In 2020, DoD awarded a $13.3 billion contract to Northrup Grumman to start the design and testing of the Sentinel.7 The initial plan was to replace the MMIII missiles by 2036. In 2024, the Air Force informed Congress that the Sentinel program had caused a Nunn-McCurdy breach of cost and schedule. Part of the problem was realizing that the assumption that they could reuse the MMIII missile silos was … absolutely wrong. Now the Sentinel fielding may take up to 2050.

I get it that this is an incredibly complex program. But for fuck’s sake, Air Force, you had as a minimum TEN YEARS to figure this out. The AF nuclear enterprise continuously moped about a “twenty-year acquisition holiday” as their plans for modernization kept getting kicked down the road (counting from the end of the Cold War to the stand-up of Air Force Global Strike Command). But I see little evidence of the Air Force putting competent people in charge of managing acquisition programs and (dare I say it) developing operational concepts that the Air Force can afford and realistically implement. Maybe I’m reaching, but if I had to worry about a multi-billion-dollar major defense acquisition program, I would make damn sure that it had the adequate staff and planning to hit its cost and schedule objectives within reason. And I would ruthlessly cull those people who could not navigate the defense acquisition system to make sure that one of the department’s top defense priorities wasn’t on track.

This useful idiot, while at the Air University. once wrote a piece arguing for a rational approach to nuclear weapons policy. He said “The idea that we can’t afford to modernize the nuclear triad, plainly speaking, is just not credible. Of course we can afford this capability.” He was so young, so naive. In a sense, all the talk about “affording” nuclear weapon modernization is a moot political point because Congress doesn’t care about the cost and schedule of certain defense acquisition programs. If you need any more evidence as to this attitude, take a look at the horribly constructed Golden Dome behemoth that is slouching toward Bethlehem. But it would be nice to have AF acquisition professionals who think about staying on budget.

Around that same time as that article, the Air Force deputy chief of staff for strategic deterrence and nuclear integration (AF/A10) announced this concept of developing “thought leaders” for the AF nuclear enterprise. And by “thought leaders,” he meant AF officers who were articulate enough to convince the rest of the Air Force and DoD that nuclear weapon modernization was necessary. Yes, there are a lot of Air Force leaders who don’t believe in nuclear deterrence. He wanted cheerleaders, not critical analysts and writers. He missed the entire concept of what was necessary to communicate the AF nuclear deterrence mission, but he was a three-star general and I was just a dumb AF civilian.

But hey, whatever you do, don’t look at the Navy’s ballistic submarine modernization program. They really mean it when they call themselves “the silent service” in that the Navy boomer community does not want you to look at or talk about the significant cost and schedule inflation of the Columbia-class boats that make up the third leg of The Triad. In 2017, the Navy estimated that the average Columbia-class boat would cost $7 billion each. That grew to $9 billion in 2021 and now is sitting at about $10 billion a pop.8 The first boat was supposed to be completed by 2027, but unsurprisingly, will now be closer to 2029-2030. From a year ago:

A new independent audit of the Columbia-class submarine program shows the Navy is struggling to contain the price of the shipbuilding program with cost overruns reaching “six times higher than” the prime contractor’s estimates and “five times more than the Navy’s.”

“As a result, the government could be responsible for hundreds of millions in additional construction costs for the lead submarine,” according to a Government Accountability Report published today.

The Navy’s ballistic submarine modernization program has always cost much more than the AF ICBM modernization program. But Congress doesn’t care about the Navy’s going over budget and being behind schedule, because the Navy does need to replace those aging Ohio-class ballistic submarines. All the Navy admirals have to say is “assured second strike” and all of the war hawks salute and say, “how much money do you need next year?”

I believe that nuclear modernization is important and should be funded (within limits). I also believe that the Air Force and Navy need to think long and hard about what they say is their services’ top defense priority. They’ve been doing a right shite job right now and the DoD leadership ought to drag them for it (but they won’t). This is important work and all of the fancy talk about deterrence theory doesn’t matter if the DoD can’t manage upgrading its capabilities after Congress has fully funded them.

This critique is primarily meant for those generally interested in defense topics and not for the DoD nuclear enterprise. They know what they’re doing and the problems they face. For those more engaged in nuclear deterrence discussions, let me leave you with a strong recommendation to read this War on the Rocks article, “Don’t Make a Submarine-Launched Cruise Missile a Priority” by Dr. John Maurer. He’s at the Air University teaching SAASS students about nuclear strategy, and he has a very balanced argument and articulate thoughts on the subject. I would make this article a separate post, but I agree fully with him and have nothing additional to add, so just go read the article.

I mean, in comparison of nuke-bio-chem, of course. The real defense priority is evidently blowing up civilian boats in the Caribbean and spending billions on gold-plated defense systems that don’t support conventional warfare, but details…

DCA refers to “dual-capable aircraft” that can load either conventional or nuclear weapons. Pretty much limited to fighter aircraft, e.g., F-15, F-35, Tornado, although technically speaking, strategic bombers are “dual-capable.”

Answer, AF officers don’t manage escalation, that’s a political component. They may have thoughts as to what might constitute or lead to escalation.

The Army and Marine Corps do care about this issue but also do not want to debate their OSD masters as to the inadequacy of CBRN defense capabilities in light of a potential theater nuclear conflict. Some bullshit about “civilian control of the military” that they think applies to low-ranking SESs. The Navy doesn’t care at all, because they intend to move their ships away from the contamination.

Seriously, I want to know who in the AF/A10 shop came up with and who approved this amazingly outdated language. It’s not hard if you actually read JP 3-11 and JP 3-40.

In my opinion only, the GAO excels in data collection and presentation but falls short on strong policy recommendations. They used to be better.

The Sentinel team includes Northrop Grumman, Bechtel, Aerojet Rocketdyne, Clark Construction, Collins Aerospace, General Dynamics, HDT Global, Honeywell, Kratos Defense and Security Solutions, L3Harris, Lockheed Martin, Textron Systems, as well as hundreds of small and medium-sized companies from across the defense, engineering and construction industries.

The first boat will cost $15 billion, which may include some sunk costs (not trying to be funny) associated with R&D and test and evaluation. Used to be set at $13 billion for the first boat.

Al, I just completed an AO review of the Army's ATP 3-72 Nuclear Ops. It is as bad as the AF 3-72. I had 25 comments that included how the draft publication did not focus enough on protection from nuclear effects, how to conduct CNI or CSNO at a tactical level, or even what tactical leaders should consider for enemy use of nuclear weapons. It is a sad pub in it's current state. Cold War era 3-72s are written much better. I hope USANCA corrects some of the issues I pointed out and releases it at an unclassified level and not CUI. I agree with your assessment that the AF has no idea what CBRN defense is as I routinely have discussions on what they can do and what they can't and if they require assistance, what do they expect. Great article.