I’m going to try something new. I want to discuss the challenges of developing policy and programs that address unconventional weapons with respect to national security. The title of this Substack is “Nuclear Weapons (and other WMD).” This is an intentional play on what I usually see in contemporary national security discussions - that of course, nuclear weapons are important and deserve a lot of discussion and debate as to how they are developed and employed, and certainly nuclear weapons are “weapons of mass destruction.” But then there are those “other WMD.” Policy makers and politicians generally relegate chemical and biological weapons to that “other” category, because let’s be honest, they don’t have the impact or panache that nuclear weapons do. Ever since the U.S. government gave up its chemical and biological weapons, the policy makers’ interest in those systems accordingly dropped.

For a while, the hypothetical that a non-nuclear country (such as Saddam’s Iraqi regime) might employ chemical or biological weapons against the U.S. military created enough heat that the concept of counterproliferation ignited a series of discussions on how such capabilities might be formed. This gradually turned into combating WMD and then countering WMD (there was no real difference there, but hey, politics). And then, as we got further away from the 2003 invasion into Iraq, people stopped talking about WMD as a necessary defense capability. I talked about this phenomenon in this Nonproliferation Review article in 2019.

In the past five years, the neglect of countering WMD or counterproliferation policy has only gotten worse. With the exception of the National Defense University’s Center for the Study of WMD, few if any think tanks discuss the issue outside of an arms control perspective. It’s not a topic in the service war colleges and even at NDU, that center is having challenges staying open for business. The leaders of the armed services, both military and civilian, do not discuss the topic in their annual posture statements to Congress. The combatant commands don’t talk about the issue in any depth. While U.S. Special Forces Command took up the advocacy role in 2016, it remains unclear as to its ability to deliver any significant progress in developing new capabilities or influencing defense strategy. But they do host nice conferences at MacDill AFB (below picture is a 2023 conference).

Now chemical and biological defense, sure, there’s a lot of discussion on that topic, but at a much lower level. It’s mostly trade talk, focused on widgets and responding to incidents and attacks; it exists in a small niche within Washington DC and doesn’t get much light. The Army Chemical Corps will always talk about the need for CBRN defense and the Air Force will always worry about installation CBRNE response, but no one really cares at the upper levels of national security policy. It’s a tactical focus within a small community that doesn’t influence national strategy or policy, and those DoD officials responsible for counter-WMD strategy don’t really engage the CBRN defense people in policy or resource advocacy. It would take more time to discuss why this particular disfunction exists.

But I digress. Nuclear weapons are always an interesting and topical issue, for many reasons, mostly because they represent the one true existential threat to the United States and any other industrial nation. And this is not a new feature, countless articles, meetings, and strategy documents discuss the dangers of nuclear weapons, how they could essentially end civilization, and at the same time, why the United States needs more or less of these unique weapons. There are much smarter, more eloquent people out there than I who engage on nuclear deterrence and nuclear modernization issues every day. And yet, I think there are more discussions needed here. Our military members don’t understand the concept of nuclear weapons employment, and often eschew the issue because it just isn’t relevant to their daily operations in a conventional military scenario. My last job was at the Air War College, and I can’t tell you how many very talented and smart Airmen came through Maxwell AFB with little to no understanding of what the DoD nuclear enterprise is or does.

The DoD nuclear enterprise, along with its DOE partner, spends billions of dollars every year on maintaining and modernizing its nuclear arsenal. I believe this modernization is necessary and overdue, even if it is plagued by inefficiencies and cost overruns. Nuclear weapons catches the attention of policy makers and politicians like nothing else, especially in this time where the U.S. military is attempting to modernize every delivery system and its command and control structure. China and Russia see this and they want to stay up with the competition, which fuels all sorts of interesting discussions across the Internet. And we need this discussion, even as people routinely misuse the term “deterrence” and insist that they have the correct solution for strong U.S. deterrence. Go to the “War on the Rocks” page and search for “deterrence,” and you’ll see what I mean.

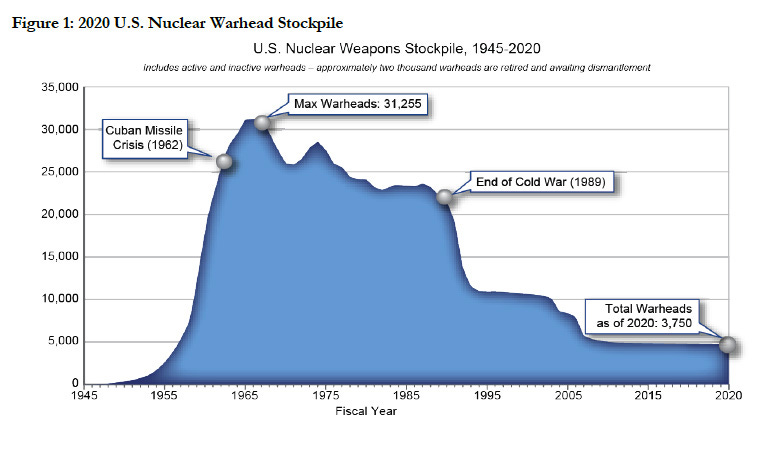

It’s often difficult to talk about nuclear weapons in any but the most generic sense, since the DoD classifies so much information about yields, locations, capabilities, plans and concepts. Sure, I get it, the most existential threat to civilization requires a degree of secrecy because we don’t want adversarial nations to gain an edge on the United States, which has been in this business since the 1940s. At least we’re back to seeing what numbers of warheads are still in the U.S. stockpile, a fact that vanished during the Trump administration. At the least, it’s a good graphic for making the point that it isn’t the Cold War anymore.

The funny thing, maybe an absurd thing, is that you might think that the people who work with and discuss nuclear weapons would be a kindred spirit to those in the counter-WMD community. But they’re not. Nuclear operators are special. Everyone else is a lesser concern and should be treated as such. There is no synergy between the nuclear community and the counter-WMD or CBRN defense community. U.S. Strategic Command proved that point when they lost interest in advocating for WMD policy and programs in 2016. One is a strategic concern to policy makers and the other is an insurance policy for those military forces who might face chemical or biological weapons. I believe that, to a strong degree, there are many policy makers and politicians who see the possession of nuclear weapons as the ultimate guarantor against a nation using chemical or biological weapons against U.S. forces. So why bother with putting any significant money into counter-WMD capabilities?

There is a way to analyze and discuss these issues, which is through examining the policy process by which these programs move forward. I became interested in public policy when I wrote my book on the U.S. chemical demilitarization program, and I used this book by Charles O. Jones, “An Introduction to the Study of Public Policy,” as my methodology to do so. I repeated this process in two other books to illustrate how the U.S. government in general, and the DoD in particular, addresses counter-WMD policy and programs. It’s a wonderful book that really opened my eyes as to how the machinery of government works (or doesn’t work) on any area that receives federal funding. In short, Jones notes that there are four specific groups of people engaged in policy making. There are the policy makers who are supposed to develop rational policy, but often do not consider the political aspects of the challenge. There are the technicians who are the subject-matter experts who have to implement government programs, very smart people who sometimes fail to grasp the intricacies of policy-making. There are the congressional legislatures who fund the programs but only in an incremental fashion and who can whipsaw the progress of an issue back and forth. And there are the non-governmental critics, to include think tanks and advocacy groups, many of which have agendas that ignore politics or funding constraints. How these groups take on a policy issue and how they cooperate or disagree on points determines the success of any public policy program.

Without getting too far into this discussion today, I just want to identify the methodology that I will use to discuss nuclear weapons issues and counter-WMD policies and programs. I plan to comment on current issues in the news, to include the op-eds and points made by people in this business. I may throw in a book review every now and then. I believe this discussion is vitally necessary today because we have a very large population of military and civilian personnel who have grown up post-9/11 and who have little to no insights as to how nuclear weapons and counter-WMD policies were made and who do not see how the really bad decisions and discussions influence them as they prepare for future military scenarios. I have spent a long career in this area, and I don’t believe that LinkedIn posts are adequate to identify the problems that they face. I hope you’ll join me in this future endeavor.

I just found this section in the NDAA for 2022 dated December 27, 2021"

(7) The term ‘‘non-kinetic threats’’ means unconventional threats, including—

(A) cyber attacks;

(B) electromagnetic spectrum operations;

(C) chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear effects and high yield explosives; and

(D) directed energy weapons.

I'm not sure how "high-yield explosives" are at the same time "non-kinetic threats" but okay.

The spectrum of “acceptable” weapons is shifting again with the Russian invasion of Ukraine seemingly rehabilitating land mines and cluster munitions and the deliberate targeting of civilian infrastructure. With manpower shortages likely to continue to grow the pressure to use other means will increase.